Struggling to create library call numbers that actually make sense? You’re not alone. The LC Cutter Table transforms author names and titles into systematic codes, but without the right approach, it becomes a maze of numbers and exceptions. This guide breaks down exactly how to use cutter tables for consistent, logical filing every time.

You’ll learn the precise rules for vowels, consonants, and special cases—plus the insider techniques librarians use to avoid common pitfalls. By the end, you’ll confidently generate Cutters that work within the Library of Congress system. Whether you’re cataloging a new collection or troubleshooting filing issues, mastering how to use cutter table is essential for maintaining an organized, accessible library.

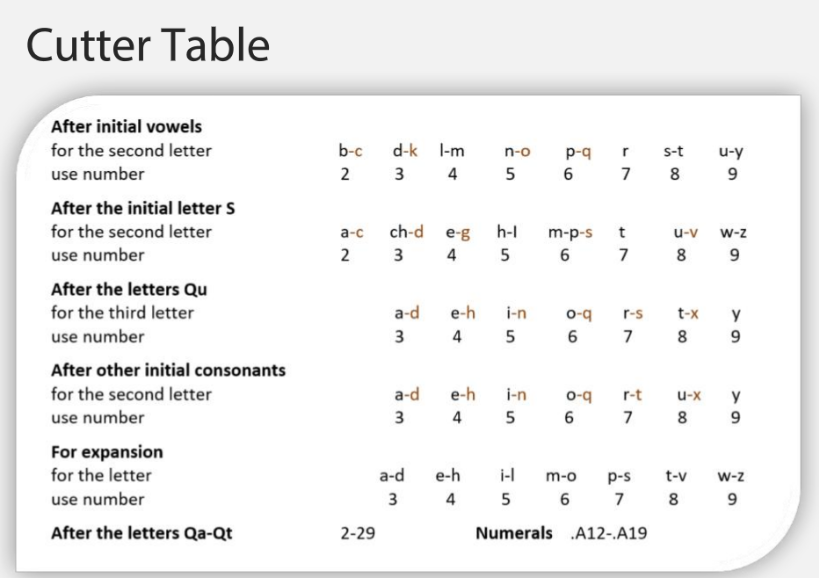

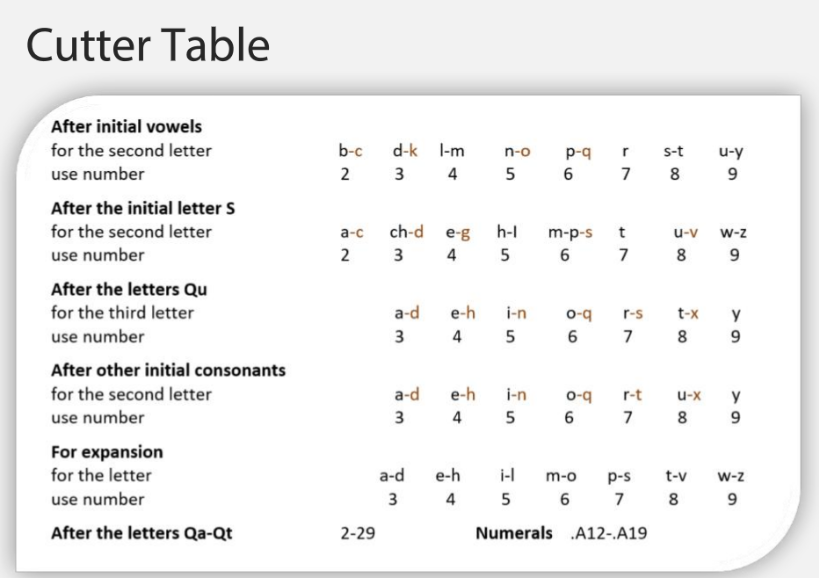

Decoding LC Cutter Table Structure: Initial Letter Rules Explained

The LC Cutter Table converts letters into numbers following the initial character, creating unique alphanumeric codes that determine filing order. Every Cutter starts with the initial letter followed by numbers representing subsequent letters. Critical rule: Cutters must never end with 1 or 0—these digits are reserved for special purposes and will disrupt your filing sequence if used incorrectly.

Think of the Cutter as a decimal translation system where your author’s name becomes a precise filing location. The first letter stays as-is, while each following letter gets assigned specific numbers based on its position. This creates a logical sequence that makes alphabetical order visible in numerical form on your shelves. When properly applied, how to use cutter table ensures materials file in perfect alphabetical order without gaps or overlaps.

Why Cutter Numbers Never End with 1 or 0

This seemingly small rule prevents major filing disasters. Ending Cutters with 1 or 0 creates ambiguity in the decimal system—should .C30 come before or after .C3? Following this rule eliminates confusion and maintains consistent spacing between entries. If you need to adjust a Cutter for filing purposes, always end with 2-9 to preserve the integrity of your shelflist.

How to Cutter Words Beginning with A, E, I, O, U, or Y

When your author’s name or title starts with a vowel, use these specific second-letter rules to generate accurate Cutters. This vowel-starting pattern is one of the most common scenarios you’ll encounter when learning how to use cutter table effectively.

Vowel-Starting Words: Second Letter Conversion Chart

| Second Letter | b | d | l-m | n | p | r | s-t | u-y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutter Number | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Real-world examples you can apply immediately:

– IBM becomes .I26 (I + b→2 + 6 for expansion)

– Idaho becomes .I33 (I + d→3 + 3 for expansion)

– Ilardo becomes .I4 (I + l→4 with no expansion needed)

– Import becomes .I48 (I + m→4 + 8 for expansion)

– Inman becomes .I56 (I + n→5 + 6 for expansion)

Pro tip: When the second letter falls between l and m (like “lardo”), always use 4 regardless of the specific letter. This prevents inconsistent filing that would disrupt your collection’s organization.

Special S-Starting Words: Mastering LC Cutter Table Exceptions

Words beginning with S follow unique rules that differ from standard consonant patterns. Knowing these S-specific exceptions is crucial when you need to use cutter table for common author names and titles.

S-Initial Words: Second Letter Conversion Chart

| Second Letter | a | ch | e | h-i | m-p | t | u | w-z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutter Number | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Key distinction: Notice how “ch” counts as a single unit here, unlike other consonant combinations. This prevents misfiling of common names like Schreiber.

Practical applications:

– Sadron → .S23 (S + a→2 + 3)

– Scanlon → .S29 (S + c→2 + 9)

– Schreiber → .S37 (S + ch→3 + 7)

– Shillingburg → .S53 (S + h→5 + 3)

– Stinson → .S75 (S + t→7 + 5)

Q and Qu Words: Navigating LC Cutter Table’s Tricky Exceptions

The letter Q creates two distinct scenarios that trip up many librarians when they first learn how to use cutter table. Master these Q-specific rules to avoid common filing errors.

Qu Combinations: Second Letter Conversion

| Second Letter | a | e | i | o | r | t | y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutter Number | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Qa-Qt Combinations: Sequential Numbering

For words beginning with Qa through Qt, use numbers 2-29 in sequence rather than the standard pattern.

Real examples to follow:

– Qadduri → .Q28 (Qa-Qt range)

– Quade → .Q33 (Qu + a→3 + 3)

– Queiroz → .Q45 (Qu + e→4 + 5)

– Quinn → .Q56 (Qu + i→5 + 6)

Standard Consonant Patterns for Perfect LC Cutter Numbers

For most author names starting with consonants (B, C, D, F, G, etc.), use this straightforward pattern when you need to use cutter table for standard cataloging.

Standard Consonant Second-Letter Conversion

| Second Letter | a | e | i | o | r | u | y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cutter Number | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Common examples in practice:

– Campbell → .C36 (C + a→3 + 6)

– Ceccaldi → .C43 (C + e→4 + 3)

– Cobblestone → .C63 (C + o→6 + 3)

– Cryer → .C79 (C + r→7 + 9)

Cuttering Numbers: Converting Numerals to LC Call Numbers

When cataloging works with numeric titles or corporate headings, use the special .A12-.A19 range for numerals. This technique is essential when you need to use cutter table for government documents, reports, and numbered series.

Best practice: Start with .A15 for the first numeral in a class, leaving room for both smaller and larger numbers. This prevents filing conflicts as your collection grows.

Example application: The number “2024” might become .A152 when cuttered, with the 2 representing the first digit in the available numeric range. Always check existing shelflist entries first—some classifications use document numbers like .A5 for corporate headings.

Beyond Basic Cutters: Adding Precision with Expansion Numbers

When multiple works share the same author or you need additional filing precision, use the expansion table to add extra digits to your Cutter number. This advanced technique ensures your collection maintains proper alphabetical order.

Expansion Letter Ranges

| Letter Range | a-d | e-h | i-l | m-o | p-s | t-v | w-z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expansion Number | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Space planning technique: If .C36 already exists, don’t automatically use .C37—consider .C365 to allow for five additional entries between them. This strategic spacing prevents future reorganization headaches.

Critical LC Cutter Errors That Break Your Library’s Organization

Avoid these common mistakes that undermine your collection’s organization when you use cutter table:

Three Fatal Cuttering Mistakes

- Ending Cutters with 1 or 0 – This creates filing ambiguity and disrupts your entire sequence

- Ignoring existing shelflist patterns – Always check what’s already filed before creating new Cutters

- Poor spacing decisions – Failing to leave room for future additions forces constant reorganization

Pro tip: When multiple works share the same author, use birth years or work titles for differentiation rather than cramming everything into the same Cutter number.

3-Step Verification to Ensure Your LC Cutter Numbers File Correctly

Before finalizing any Cutter number, follow this verification process to guarantee proper filing order:

- Scan the shelflist for existing similar entries and established patterns

- Check temporary placement by physically testing where the new Cutter would file

- Verify spacing adequacy by ensuring room for at least 3-5 future additions

Quick test: Place your new Cutter between two existing entries. Does it maintain logical alphabetical order? If not, adjust the final number accordingly before finalizing.

Complex Cutter Scenarios: Multiple Authors, Translations & Series

When you’ve mastered how to use cutter table for basic cataloging, tackle these advanced situations with confidence:

Handling Special Collections

- Multiple authors with same name: Use birth years for differentiation (e.g., .A562 1980)

- Translated works: Cutter for original title, not translation

- Series works: Cutter main work, then add series position numbers

Expert advice: Maintain a local adjustment log. When you deviate from standard rules for practical filing reasons, document the decision for future consistency across your collection.

Master the LC Cutter Table by practicing with real examples from your collection. Start with simple author names, then progress to complex titles and corporate entries. Remember: standard rules provide the foundation, but local practice and existing shelflist patterns guide final decisions. With this guide on how to use cutter table, you’ll transform confusing cataloging challenges into perfectly organized collections that serve your patrons effectively.